Many students struggle to have a growth mindset toward writing. They don’t like it or they don’t think they’re good at it, and year after year, the writing process remains a mystery.

However, as a teacher you know writing is essential to students’ future. Nearly every career requires written communication, and the better you are at it, the better your chances at succeeding in life. That’s why it’s critical to show students that writing is a skill anyone can master, regardless of natural ability or interest.

Dr. Peter Elbow(Open Link in new tab) has spent decades democratizing the writing process, making a way for every student to enhance their critical thinking and craft stronger essays. Countless teachers have turned to him for writing pedagogy advice, and here, we’ve compiled several of his best handouts. You can find these and a treasure trove of additional resources on his website(Open Link in new tab).

Writing for Learning—Not Just Demonstrating(Open Link in new tab)

This piece discusses two different kinds of writing: (1) writing to learn and explore a topic and (2) writing to demonstrate understanding. Most of the time, schools focus on the latter; we assign high-stakes essays in which students must show their mastery of both writing conventions and the topic at hand. However, writing to learn is an often-untapped pedagogical technique that naturally strengthens students’ skills for high-stakes writing. According to Dr. Elbow:

- Writing inherently helps with understanding and retention. According to Dr. Elbow, “We tend to think of learning as input and writing as output, but it also works the other way around.” In other words, the act of writing itself—even if it isn’t “good” writing—will help students learn about a topic.

- You don’t have to grade every piece of writing. When students write to learn, they’ll be writing more than you could ever hope to grade (or even read). But that’s okay. Writing itself is beneficial, so you don’t have to critique everything students produce.

- Writing doesn’t have to take time away from course material. Rather, you can incorporate it into homework or instructional time through activities such as warmups or reviews at the beginning of class, check-for-understanding in the middle of class, or reflections at the end of class.

- Writing should take place in every subject area. Often, we think of writing as belonging almost exclusively to ELA. However, in the real world, every field requires writing and communication, and writing to learn is a great way to beef up writing opportunities in other subject areas.

- You don’t have to be an ELA teacher to teach writing. Along with the previous point, non-ELA teachers often feel hesitant about teaching or critiquing writing. However, other subject area teachers actually have unique opportunities to teach students about writing conventions in different fields.

- Writing doesn’t have to be solitary. In fact, people naturally challenge themselves to write better if they know someone else will read or hear it. You can make writing more communal simply by having students pair off and read their own writing out loud to each other.

Response Options for Peers(Open Link in new tab)

Peer feedback is an excellent way for students to grow as writers. However, without the proper direction, students might not get the insights from others that they really need to understand their strengths and weaknesses. That’s why Dr. Elbow created this guide for different ways to solicit peer feedback, each with a specific purpose. Here’s a preview of the different exercises:

- Don’t respond. Sometimes, writers just need to read a piece out loud to someone so they can think about how it sounds. This technique might be helpful for students who are particularly insecure about their writing, or when students are finished revising and want to share the final product.

- Point. There is such a thing as feedback overload. Sometimes, writers don’t need to hear the “why” behind what worked or didn’t work; they might just want to ask peers to point to parts that went well (or didn’t) so they can get an idea about what to focus on next.

- Tell me what gets through to you. Just as it’s important to know what isn’t coming off correctly, it’s essential to know what’s working well. In this type of feedback, peers spend time pointing out the strengths of a piece.

- Reply to me. Instead of focusing on writing techniques, this feedback strategy involves talking about the content: the main ideas of the piece, thoughts on the topic in general, whether the reader agrees or disagrees, etc.

- Give me movies of your mind. In other words, the writer asks readers, “What was going through your head as you read? What did you feel when you read this paragraph?” This might involve reading the piece in sections to discuss and reflect.

- Tell me specific features or dimensions. For example, students might ask about particular writing issues such as mechanics, organization, clarity, persuasiveness, etc.

Skeleton Process From Chaos to Coherence(Open Link in new tab)

Writing teachers rightly extol the virtues of freewriting, but how do you move from sloppy, stream-of-consciousness thinking to polished, well-written, and well-structured essays? In this handout, Dr. Elbow outlines two different ways to mold prewriting into an excellent final product. Here’s a preview of one of them:

- Find important passages. Read any relevant research material in whatever order you want, highlighting passages that feel important or relevant.

- Create bones. For each passage you highlighted, write a sentence summarizing what it’s about. Make sure it’s a complete sentence, not just a half-formed thought.

- Figure out a main idea. Now that you have a string of random sentences, read through them all to identify the main idea. Write it out in a complete sentence.

- Build the skeleton. Now examine your sentences and start to figure out the right organic order for your thinking. At the end, you’ll have an outline with several complete sentences to help you get started.

Grading Less, Grading Better(Open Link in new tab)

Grading less? Yes, please! In this handout, Dr. Elbow outlines how you can make your grading more efficient by (a) not grading as much and (b) making grades more meaningful. Some of his tips include:

- Don’t use letter grades. Letter grades don’t really help students know what they did well or not. In fact, they can distract students from actually learning from their work or damage their relationship with their teacher.

- Don’t grade everything. Especially with freewriting, journal writing, and similar low-stakes assignments, a simple complete or incomplete grade will do. In these cases, the important thing is that the students wrote, not how they wrote on a technical level.

- Use fewer levels of quality in grading. Both students and teachers may resist this idea, but Dr. Elbow explains how minimalist grading is not only less time consuming, but also fairer, more accurate, and better for learning in the long run.

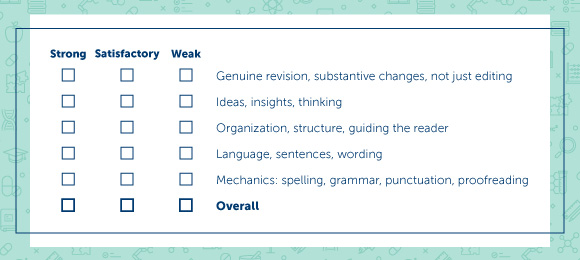

- Use a rubric. This one’s a no-brainer, but Dr. Elbow includes a handy grid that breaks down the different parts of writing and helps you provide more targeted feedback.

- Consider “contract grading.” At the beginning of his courses, Dr. Elbow laid out minimum requirements(Open Link in new tab) for earning a B in his class, including being on time, participating in group activities, and substantially revising papers (even if they decide not to incorporate certain feedback). That way, students are more likely to think critically about how to improve their work rather than just executing exactly what the teacher says.