This blog post was written by guest contributor Dr. Julie P. Jones, author of The Playful Classroom.

When most teachers hear the term play, their minds go to those few minutes at recess. Traditionally, educators have believed in a dichotomous system, where school is work and recreation is play. Thankfully, this divisive view is losing popularity as we learn more about the science of cognition and childhood development. As a result, more and more educators are inviting play and playful teaching into their classrooms.

After a year and a half of fear and instability thanks to COVID-19, kids need play now more than ever. In this article, we’ll see the healing—as well as educational—benefits of play, and how teachers can use this essential tool to help kids recover post-pandemic.

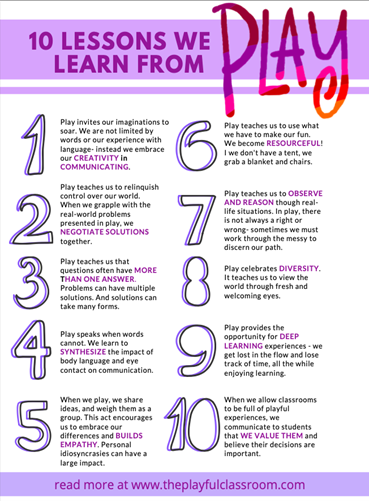

But first, let’s take a look at the top 10 lessons we can learn from play, as shown in the infographic below.

Pandemic as Trauma

Teaching and learning from Spring 2020 to present have been different from any teaching and learning in our collective living memories. For some students, life continued as normal (with the exception of mask-wearing and social distancing). For others, their whole world was turned upside down.

- They may have lost a loved one.

- They may have been sick themselves.

- They may have missed meals or stopped seeing people outside their family unit for the first time.

We all experienced uncertainty. While the COVID-19 pandemic does not fit current models of causes for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), emerging research indicates that people are showing symptoms of traumatic stress resulting from this ongoing global stressor.

Maslow Before Bloom

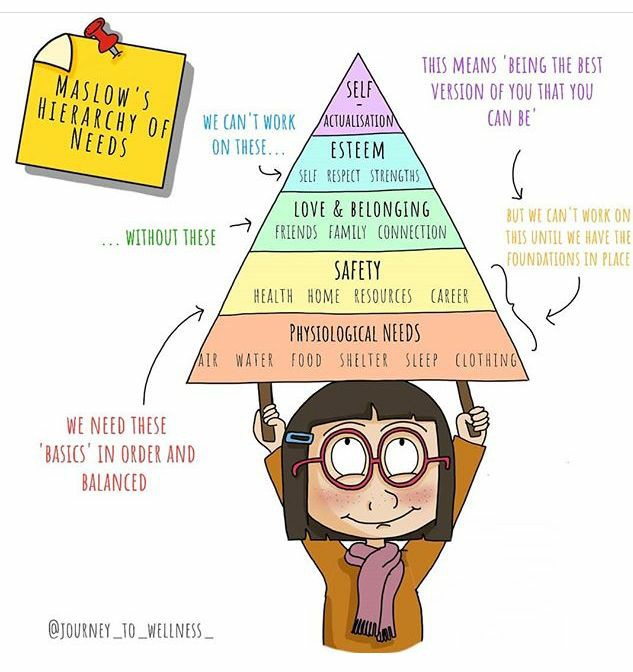

If you are one of the 57% of the global population on social media, you may have seen the phrase “Maslow before Bloom” a few times. The image below is one of hundreds I found when searching Twitter for an example.

As we move into a new academic year, I hope this article inspires educators to incorporate play and teach playfully—not only for the sake of learning, but also for the purposes of healing.

If you need a refresher on Maslow’s hierarchy, take a look at the pyramid below. At the bottom of the pyramid are our most essential needs. To move up the pyramid, one must first satisfy the levels underneath.

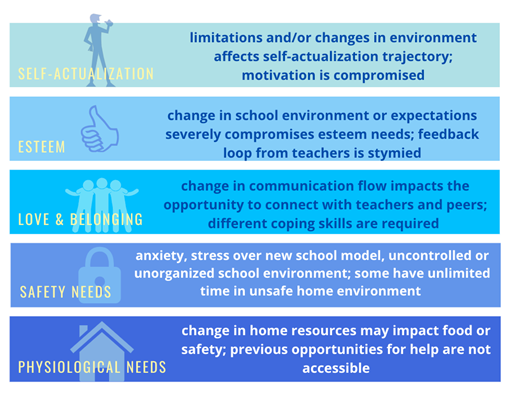

Now take a look at how the pandemic has affected many teachers and students. Many of their essential needs have been challenged in the past 18 months. Families had to face tough questions like:

- Did it become more challenging to meet basic needs thanks to job loss or other threats to your security?

- Did education change? For example, did you teach or learn in person? Did you feel safe doing so? Did you teach or learn online? Did you struggle with interacting and asking questions?

- Could you maintain your support system?

- Did your goals change? Did you find yourself rethinking what you need and want?

Play as Healing

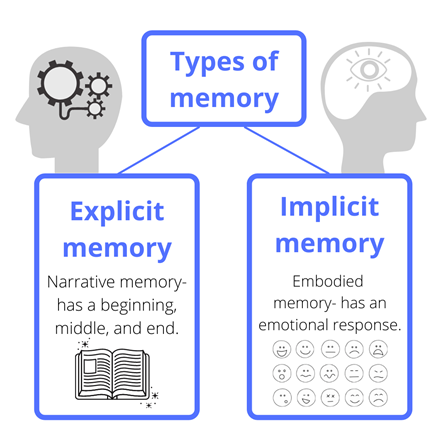

Play therapy research explains two types of memories: implicit and explicit.

Explicit memories are stored much like a narrative—there is a beginning, middle, and end when we think about the memory.

In contrast, implicit memory is embodied memory. In other words, when recalled, the memory manifests in our bodies as if it’s happening now. You know how this goes: Holidays are better when you smell pumpkin pie or salted caramel (hello, candle companies). Or you hear “Thriller,” and you are immediately back in middle school dancing it out with your besties.

As research related to the pandemic continues to emerge, we’re seeing the impact of pandemic experiences on our implicit memories. Isolation, lack of socialization, and lack of variety in our daily routines have all contributed to a decrease in memory and an increase in anxiety and depression. In real terms, that means we’re emotionally stuck reliving the emotions of pandemic hardships, without the ability to move on or feel like there’s an “end,” as we do with explicit memories.

However, when we play, the neurotransmitters our brains release help us move toward balance—the exact opposite of the disequilibrium brought on by the pandemic. Safe relationships, experienced during play, allow students to release a preconceived agenda (here, pandemic trauma) and instead write new scripts about life and their experiences in the world.

Here’s the cool part—are you ready for it?

These new scripts, or new understandings of relationships and community, overwrite and rewire neural circuitry, resulting in healing. Those implicit memories that so affected us before now shift into explicit memories. In other words, we stop feeling the pandemic traumas as if they’re happening right now, and instead we construct a narrative of these experiences as being part of our past, without the significant emotional response. Read that again. Without the emotional response. That’s healing.

Great. Sign me up. What’s the ETA on healing?

Sorry to be the bearer of not-so-great news. This approach, while effective, is not a quick fix. Healing takes time. As Siegel says in The Developing Mind: How Relationships and the Brain Interact to Shape Who We Are, for those of us who have deeper struggles, the window of tolerance for strong emotions may be narrow. However, as you build trust, with small nudges over time, you can help your students move toward healing.

So what separates traditional pedagogy from playful pedagogy?

When we invite student choice into our classrooms and empower students to make decisions on how to showcase their learning, we show students that we trust them and value their input. We are encouraging new ideas and approaches while also building relationships. Through these relationships, we offer our students experiences of autonomy, competence, and relatedness, which hundreds of studies have shown result in improved psychological well-being.

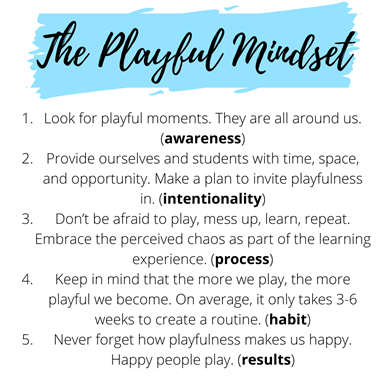

Developing lessons that incorporate play and a playful mindset is not a linear process. Rather, it’s like a game of Frogger. Students and teachers won’t be able to exercise these muscles until given the time, space, and opportunity to play with concepts. In fact, it is through play that we are most creative. As I write about in my book with Jed Dearybury, The Playful Classroom: The Power of Play for All Ages, the playful mindset consists of awareness, intentionality, process, habit, and results.

Having a playful mindset helps us move toward having playful classrooms. And don’t we all want to engender learning and health through play and creativity?