Systemic change might not be realistic.

Changing the institution of public education is a tall order. The problem with systemic change is that schools are designed to reflect our contemporary society. They are susceptible to shifting political climates, global competition, and economic volatility.

For education reforms to succeed on a systemic level, they must withstand the pressures of a rapidly changing political landscape. Paradoxically, the structure of public education is actually very resistant to change. Schools maintain their historic resemblance to factory lines with bells and neat rows of desks and their prioritization of rote memorization, yet the demands on our educational institutions are in constant flux. Education, comparable to our Constitution, is designed to be resistant to change, yet must remain applicable to an evolving society, requiring our continual reinterpretation.

If this is the case, we need to consider education reform on a much smaller scale. We should view schools as reflections of smaller communities woven into the fabric of American society at large. What if we considered schools as a type of small, local business? How does a local business develop a strong business model that is both resistant and adaptable to fluctuations in consumer behavior? Successful businesses are able to weather any storm, but in order to reach that level of resilience, they have to be clear on who their customers are, what their vision and mission is, and how they will manage their operations. Only once these criteria are met can they consider scaling the business.

With this framework, it’s easy to draw a connection between charter schools and local businesses. Charter schools need a founding vision and mission – an educational philosophy, a curriculum approach, and a target student population. They must decide on their legal structure – whether they want to operate as a nonprofit or a for-profit, similar to how a local business would need to decide on being an LLC or a corporation. Charter schools also need to uphold an accountability plan to prove they are meeting the standards of the charter to keep their doors open, which is not unlike the pressures of a local business complying with tax filings or labor laws. Both institutions require a sustainable structure that can support growth and that aligns with the community’s needs.

If we can build innovative schools that meet the needs of their students and successfully empower communities to reach their fullest potential, why wouldn’t we just focus our efforts here and forget about trying to change the public education system as a whole?

The answer is… it’s complicated. We cannot afford to abandon public education, nor should we attempt to, but I do believe that charter schools provide a good starting point for reimagining education reform from the ground up. And when we can’t afford to wait for federal policies to be implemented—only to watch them fall short, as with No Child Left Behind’s failure(Open Link in new tab) to improve national math and reading proficiencies—charter school solutions can seem increasingly appealing.

The Charter School Controversy, Unpacked

Charter schools are considered “bad,” but this might be due to an over-focus on bad actors

When we criticize charter schools for draining resources “from already stretched-to-the-limit [public] education budgets,”(Open Link in new tab) what are we really saying?

First, public schools are funded primarily through property taxes (this opens up a whole other discussion on how this is inherently inequitable in the first place, but we will save this for another time), as well as state and federal funding. While there are many funding mechanisms, per-pupil funding is of particular importance to this discussion. If public school school populations decline as students choose charter schools, funding for that school decreases accordingly.

Meanwhile, charter schools are operating in what I call an “in-between-private-and-public” space. In other words, they are “publicly financed but privately operated(Open Link in new tab),” and the private companies operating them end up profiting.

Wait, what?

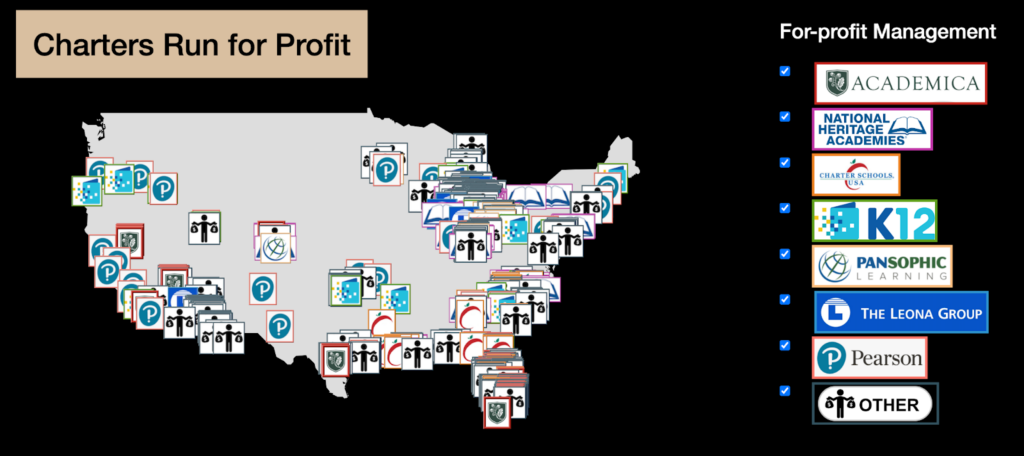

Nonprofit charter schools are considered public schools, meaning they receive federal, state, and local funding just like traditional public schools. However, their management structures can vary significantly. While 32% of charter schools(Open Link in new tab) are managed by CMOs (Charter Management Organizations) and 11% are managed by EMOs (Educational Management Organizations, typically private companies), the majority—57%—are freestanding, meaning they operate independently and manage their own operations without outside management.

But despite the fact that most charter schools are freestanding, conversations about charter schools often focus disproportionately on those managed by EMOs and CMOs. This focus can skew the broader discussion, as it overlooks the different operational models that exist. Critics of charter schools are usually unknowingly focusing on EMOs, which definitely do warrant criticism.

EMOs provide services such as rent for the property, equipment, and facilities, in exchange for the school’s revenue. In some cases(Open Link in new tab), huge organizations, such as National Heritage Academies (NHA), even control faculty employment and curriculum.

Here’s an excerpt from an NHA contract(Open Link in new tab):

“Under the terms of the Agreement, NHA receives as remuneration for its services an amount equal to the total revenue received by the Academy from all revenue sources.”

Organizations like NHA are notorious for corrupt schemes that allow them to upcharge the school for rent in order to make a profit. For example, at an NHA-managed school in Brooklyn, state auditors were “unable to determine … the extent to which the $10 million of annual public funding provided to the school was actually used to benefit its students.”(Open Link in new tab)

The Network for Public Education(Open Link in new tab) conducted a study that estimated that 1 in 7 charter schools are run in this way. According to the study, that also means 600,000 students, or 18 percent of students in charter schools, are educated in these schools operated by a for-profit corporation (colloquially coined “Run For-Profit” schools).

From here, it is very clear why critics of charter schools have so much to say. But what about the others that are run by actual nonprofit organizations?

How inequity is built into the “choice” that charter schools offer

It is true that charter school students are outperforming(Open Link in new tab) public school students. This is a good thing. However, what about the students who are left behind—those who don’t get into charter schools through the lottery system, whose parents may not speak English and struggle to navigate the application process, or those who immigrate to the United States mid-year? We must consider whether we are truly improving education for all students. If we focus solely on charter schools and neglect the broader public education system, we risk missing the opportunity to invest in the education of millions of other students.

Charter schools began to emerge across the country in the 1990s, a period when market-based reforms were gaining momentum in education. Policymakers, entrepreneurs, and philanthropists saw an opportunity to transform the education system into a “competitive market.” The idea was that the competition from charter schools would push public schools to improve as they competed for students.

But this largely ignored “the broader context in which educational interventions operate.”(Open Link in new tab) It overstepped the institution of public education, neglecting any consideration of school improvement “in concert with housing, transit, and economic development policy.” The market–based policies under which charter schools operated, therefore, ended up perpetuating the historical disinvestment in public schools. Sure, low-income and minority students are given the opportunity to choose where they attend school, but this overlooked the root of the problem: why is the originally assigned public school not a viable option in the first place?

Critics view this approach as a “rejection of the common school ideal.”(Open Link in new tab) It undermines the traditional concept of public education as a shared community resource, shifting the focus toward individual choice rather than collective responsibility. Policymakers, donors, and advocates have reshaped urban public education to function more like a private market, where parents choose schools based on perceived quality. Instead of being guided by school district oversight, education is increasingly delivered by a variety of independent providers competing for students and their data, emphasizing competition over collaboration.

How do we move forward, knowing this?

The autonomy and flexibility that the charter model offers schools cannot be overlooked. Charter schools have paved the way for innovative approaches to learning that have improved student outcomes and loosened the rigid educational standards that breed tiresome conformity over creativity.

When I worked at a charter school in Northern California, I was thrilled to be able to adapt curriculum that was made with my particular group of students in mind, as opposed to mechanically adhering to a set of state standards. With more autonomy, I could become more innovative in the classroom. I introduced new books, conversations about current events, and projects that helped my students explore their identities at a pivotal time in their lives before graduating high school and moving on to college or careers.

This is not to say that charter schools are without their own challenges and limitations. Too often, I found myself lowering standards for my students because school administrators prioritized positive data on student performance. I witnessed similar practices in public schools – as long as we hit our data goals, the students who had clearly failed their classes were being advanced to the next grade.

Nevertheless, Charter schools expand our vision of education’s potential. They demonstrate that schools can be spaces for experimentation, where teachers become innovators and students think like entrepreneurs, moving beyond merely learning to pass state tests. These schools can swiftly adapt to changing environments, foster deeper parent engagement, and better prepare students for an ever-evolving world.

While operating on a smaller scale, charter schools act as disruptors to the educational landscape, envisioning new approaches that challenge the status quo. Through their innovative practices, they have the potential to inspire broader systemic change in education.

About the Author

Evie Elson is a 2026 MBA/M.Ed. Candidate at the University of Virginia, where she focuses on applying innovative business strategies to education reform. With four years of teaching experience across Title I public and charter schools through Teach For America, Evie’s work has appeared in academic publications and she regularly writes about education innovation on Substack.

Evie is passionate about classroom innovation, competitive teacher pay, and building equitable systems that prepare students for future technological change. Her work bridges the gap between business strategy and educational excellence, drawing on her experience in high-need schools, academic research, and data-driven impact analysis in education.