Since my very first day of teaching, I’ve always preferred to focus on the hope of what students can do as opposed to the fear of what they cannot. Of course, there are limits to what any human realistically can or cannot do, but I’m increasingly frustrated by the all-too-often teacher reply of, “But my students can’t do that” when discussing changes in curriculum or creation of common assessments. However, until about seven years ago, one of my most consistent approaches to teaching was inherently grounded in a version of this very sentiment I loathed — it was just slightly softened to become, “But my students can’t do that… without my help.”

It was with this unconscious mindset that I so often employed the “I Do, We Do, You Do” strategy, providing students with a safe pathway for growth and learning through imitation. I would supportively guide students through my own thinking before letting them work with a partner or in a group to further their understanding, before finally allowing them to try the skill on their own.

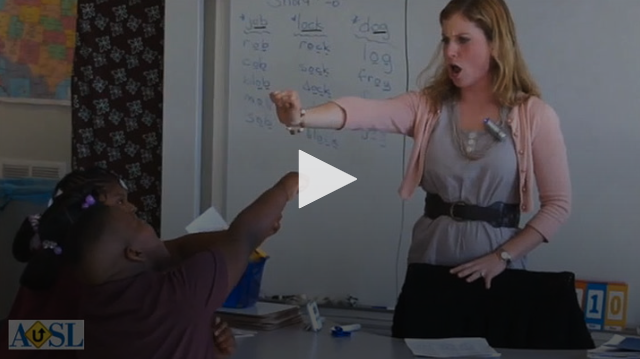

VIDEO: I Do, We Do, You Do

And then I read it…

“Mr. Bronke’s class is great. As long as you follow all the examples he gives, it is a really easy class.”

I still remember the very moment that these two simple sentences permanently pierced my teaching soul. I’d volunteered to let a previous district in which I taught test out a possible student survey, and this was some of the feedback I received.

Now in the grand scheme of feedback students can and do give, this really wasn’t a bad thing; in fact, it was a compliment on many levels — the student liked my class and found he could be successful in it. Some might say, “Isn’t that the goal of teaching?” However, I’ve never wanted student learning to be “easy” in my class.

I spent that summer reflecting upon my approach to instruction, thinking of ways to make my class more of a challenge, and that’s when it hit me,

“I need to make learning messier, less controlled, and more student-centered; in short, I need to get out of the way.”

It was at this moment that I decided to flip my approach.

- Instead of showing my students the “right way” first, and then having them work towards independence, I’d challenge them from the start to try it independently.

- From there, I’d give them time to partner or group up to compare their first attempts.

- Finally, I’d show them what it “could look like” by providing a model.

- Once shared, students would use that model to compare to their current product, self-reflecting and self-critiquing, asking questions like, “Where is my product similar to the model and where is it different… and why?”

What emerged from this flip was amazing.

I created conditions in which students were appropriately frustrated. Over time, it became known that Mr. Bronke’s class motto is,

“If you are not frustrated, you are not learning; you are simply rediscovering things you already knew.”

And the students, along with their parents, really began to buy into this.

Over the years as department chair, I’ve worked closely with teachers to help them see the benefits of this flip and better understand how to make this move, and it’s been met with initial resistance — mostly for one of the following three reasons:

- It’s hard to watch students fail — especially when you know you’re the one “causing” them to fail. For many (or hopefully all) teachers, they got into teaching because they’re nurturing and care deeply about kids, so to create lessons and a learning environment in which the teacher is intentionally pushing students to fail early on can be a challenge. Teachers find it very difficult to sit back passively while students are frustrated, and of course, it’s a balancing act. Too much frustration can lead to complete shut down; however, when done correctly, the art of sitting back and letting kids embrace and work through frustration can (and SHOULD) be at the core of great learning.

- But if “imitation is the sincerest form of flattery,” what’s wrong with giving the students the model right away and letting them imitate the “correct” way to do it? There are a few issues embedded in this line of thinking. First, in my class, we do still spend time improving through imitation, but that work is the deliberate teaching of imitation as a skill for the sake of teaching that specific skill. Being able to imitate greatness in one’s own way is its own skill, and there are days when students do sit down with an author they admire and try to write like him or her. However, that’s a different skill than learning how to write exclusively through imitation. In this model of “You Do, We Do, I Do,” students learn first through exploration, and then use imitation to refine their learning. To me, that’s real learning. Plus, learning through imitation intentionally guides them to one “right” way (the model), but learning through exploration empowers them to find THEIR right way.

- “But I just don’t feel like I’m teaching much anymore.” This last teacher response is actually my favorite because it gets at the core of my summer reflection — that I needed to get out of the way more. When teachers who have tried this strategy come back and express this concern, I reply, “Perfect!” Empowering students to learn through exploration shifts the role of the teacher from knowledge-giver to question-asker, and that’s the most essential shift we can make.

The great thing about teaching is that it isn’t a one-size-fits-all — for students or for teachers. And there is great value in a wide range of strategies, including the more traditional “I Do, We Do, You Do.” So, this piece is not meant to take away from that strategy, or any other strategy; however, if you’re looking for new ways to challenge your students, to entice them to own their learning more often and more consistently, this just might be your answer.

Have you used the “I Do, We Do, You Do” strategy in your classroom? How might your students benefit from flipping this model on its head? Let us know what’s working for you in the comments below.